What Two Conditions Must Be True For A Group Of Animals To Be Considered The Same Species

Deep in the Amazon rainforest alive two green birds. The snow-capped manakin, has a splash of white on its head. The opal-crowned manakin looks very similar. But this species' crown can appear white, bluish or ruddy depending on the low-cal. It'due south "similar a rainbow," says Alfredo Barrera-Guzmán. He is a biologist at the Democratic University of Yucatán in Mérida, United mexican states.

Feathers from the opal-crowned manakin'southward head can appear blueish, white or blood-red depending on the lite (left). The snow-capped manakin has white crown feathers (eye). A hybrid species of the two, the golden-crowned manakin, developed a yellowish head (right).

Univ. of Toronto Scarborough

Thousands of years ago, these two species of birds started mating with each other. The offspring initially had crowns that were dull whitish-grey, Barrera-Guzmán suspects. But in later generations, some birds grew yellow feathers. This vivid color fabricated males more attractive to females. Those females may have preferred mating with yellow-capped males rather than snow-capped or opal-crowned males.

Eventually, those birds became dissever plenty from the two original species to be their ain, distinct species: the gilt-crowned manakin. It's the outset-known case of a hybrid bird species in the Amazon, he says.

Unremarkably, dissimilar species don't mate. But when they do, their offspring will be what are chosen hybrids.

The molecules of Dna in each of an animal's cells hold instructions. These guide what an brute looks like, how information technology behaves and the sounds it makes. When animals mate, their young get a mixture of the parents' DNA. And they can cease up with a mixture of the parents' traits.

If the parents are from the aforementioned species, their DNA is very similar. But DNA from different species or species groups will have more than variations. Hybrid offspring get more diversity in the Deoxyribonucleic acid they inherit.

So what happens when the DNA of two brute groups mix in a hybrid? There are many possible outcomes. Sometimes the hybrid is weaker than the parents, or doesn't even survive. Sometimes it'south stronger. Sometimes it behaves more like one parent species than the other. And sometimes its behavior falls somewhere in betwixt that of each parent.

Scientists are trying to empathise how this process — called hybridization (HY-brih-dih-ZAY-shun) — plays out. Hybrid birds may take new migration routes, they constitute. Some hybrid fish appear more vulnerable to predators. And rodents' mating habits may affect what their hybrid offspring can consume.

2 bird species, the snow-capped manakin (left) and opal-crowned manakin (right), mated to produce hybrids. The hybrids eventually became their own species, the golden-crowned manakin (eye).

Maya Faccio; Fabio Olmos; Alfredo Barrera

Wise to hybridize?

Hybridization happens for many reasons. For instance, the territory of 2 similar types of animals may overlap. This happens with polar and grizzly bears. Members of the two groups of animals take mated, producing hybrid bears.

When the climate changes, a species' habitat can shift to a new area. These animals may come across other, similar species. The two groups may mate by accident. For instance, researchers have plant hybrids of southern flying squirrels and northern flying squirrels. As the climate warmed, the southern species moved north and mated with the other species.

When animals can't find plenty mates from their own species, they may select a mate from some other species. "You take to make the best out of the situation," says Kira Delmore. She is a biologist at the Max Planck Constitute for Evolutionary Biological science in Plön, Germany.

Scientists have seen this happen with two antelope species in southern Africa. Poachers had thinned out the populations of giant sable antelope and roan antelope. Subsequently, the 2 species bred with each other.

People can unwittingly create opportunities for hybridization, too. They might put ii closely related species in the same enclosure at a zoo. Or as cities expand, urban species may increasingly run across rural ones. People may even set loose animals from other countries, accidentally or on purpose, into a new habitat. These exotic species now may encounter and mate with the native animals.

Many hybrid animals are sterile. That ways they may be able to mate, but they won't create offspring. For example, mules are the hybrid offspring of horses and donkeys. Most of these are sterile: 2 mules can't brand more mules. Only a equus caballus mating with a donkey tin can make another mule.

Biodiversity is a measure of the number of species. In the past, many scientists assumed that hybridization wasn't practiced for biodiversity. If many hybrids were produced, the two parent species could merge into one. That would reduce the variety of species. That'south why "hybridization was often viewed equally a bad thing," Delmore explains.

But hybridization sometimes can heave biodiversity. A hybrid might be able to swallow a sure nutrient that its parent species cannot. Or maybe it can thrive in a different habitat. Eventually, it could become its own species, like the golden-crowned manakin. And that would increase — not subtract — the variety of life on Earth. Hybridization, Delmore concludes, is "actually a creative force."

Going their own way

Hybrids tin can be dissimilar from their parents in many means. Appearance is just one. Delmore wanted to know how hybrids might bear differently than their parents. She looked to a songbird called the Swainson's thrush.

Over time, this species has divide into subspecies. These are groups of animals from the aforementioned species that live in different areas. Still, when they do meet each other, they tin can nonetheless breed and produce fertile young.

Ane subspecies is the russet-backed thrush, which lives on the west coast of the U.s. and Canada. Equally its name implies, it has reddish feathers. The olive-backed thrush has greenish-brown feathers and lives farther inland. Merely these subspecies overlap forth the Declension Mountains in western North America. There, they can mate and produce hybrids.

1 difference between the ii subspecies is their migration behavior. Both groups of birds brood in North America, then fly south in wintertime. Just russet-backed thrushes migrate downward the westward coast to country in Mexico and Central America. Olive-backed thrushes fly over the key and eastern United States to settle in South America. Their routes are "super dissimilar," Delmore says.

Scientists attached tiny backpacks (as seen on this bird) to hybrid songbirds called thrushes. The backpacks contained devices that helped the researchers rail the birds' migration routes.

One thousand. Delmore

The birds' Dna contains instructions for where to fly. Which directions do hybrids go? To investigate, Delmore trapped hybrid birds in western Canada. She placed tiny backpacks on them. A low-cal sensor in each haversack helped tape where the birds went. The birds flew south to their wintering grounds, carrying the backpacks on their journey.

The next summer, Delmore re-captured some of those birds back in Canada. From the sensors' light data, she figured out what time the sun had risen and set at each indicate forth the bird's journey. The length of the twenty-four hour period and timing of midday differs depending on location. That helped Delmore deduce the birds' migration paths.

Some hybrids roughly followed one of their parents' routes. Only others didn't take either path. They flew somewhere downwardly the middle. These treks, though, took the birds over rougher terrain, such as deserts and mountains. That could be a problem because those environments might offering less food to survive the long journey.

Another group of hybrids took the olive-backed thrush's route south. Then they returned via the russet-backed thrush'southward path. But that strategy might also cause issues. Unremarkably, birds learn cues on their way south to help them navigate back home. They might notice landmarks such as mountains. But if they return by a different path, those landmarks will exist absent-minded. One result: The birds migration might accept longer to consummate.

These new data might explain why the subspecies have remained separate, Delmore says. Following a dissimilar path may hateful that hybrid birds tend to be weaker when they reach the mating grounds — or have a lower risk of surviving their yearly journeys. If hybrids survived too as their parents, DNA from the two subspecies would mix more often. Eventually these subspecies would fuse into one grouping. "Differences in migration could be helping these guys maintain differences," Delmore concludes.

Perils of predators

Sometimes, hybrids are shaped differently than their parents. And that tin can affect how well they avoid predators.

Anders Nilsson recently stumbled onto this finding. He is a biologist at Lund University in Sweden. In 2005, his team was studying two fish species named common bream and roach (not to be confused with the insect). Both fish live in a lake in Denmark and drift into streams during winter.

Explainer: Tagging through history

To report their beliefs, Nilsson and his colleagues implanted tiny electronic tags in the fish. These tags allowed the scientists to track the fish's movements. The team used a device that broadcast a radio signal. Tags that received the signal sent back one of their ain that the squad could detect.

At first, Nilsson'due south squad was interested only in roach and bream. Just the researchers noticed other fish that looked like something in between. The main difference was their body shape. Viewed from the side, the bream appears diamond-shaped with a taller middle than its ends. The roach is more than streamlined. Information technology'due south closer to a slim oval. The third fish'south shape was somewhere between those two.

Ii fish species, the common bream (left) and roach (right), can mate to produce hybrids (centre). The hybrid'southward body shape is somewhere in between its parent species' shapes.

Christian Skov

"To the untrained eye, they but await like fish," Nilsson admits. "Merely to a fish person, they are hugely different."

Roach and bream must have mated to produce those in-between fish, the scientists thought. That would brand those fish hybrids. And so the squad began tagging those fish, also.

Fish-eating birds chosen great cormorants live in the same area as the fish. Other scientists were studying the cormorants' predation of trout and salmon. Nilsson's team wondered if the birds were eating roach, bream and hybrids also.

Here'due south a roost for birds called cormorants. Researchers plant that these birds were more likely to eat hybrid fish than either species of the parent fish.

Aron Hejdström

Cormorants gobble fish whole. Afterward, they spit out unwanted parts — including electronic tags. A few years later the researchers had tagged the fish, they visited the cormorants' nesting and roosting sites. The birds' homes were pretty gross. "They throw up and defecate all over the place," Nilsson says. "It's non pretty."

But the researchers' search was worth information technology. They found a lot of fish tags in the birds' mess. And the hybrids appeared to fare the worst. For their efforts, the team found nine percentage of the bream tags and 14 per centum of the roach tags. Just 41 pct of the hybrids' tags too turned up in the nests.

Nilsson isn't sure why hybrids are more likely to be eaten. But perhaps their shape makes them easier targets. Its diamond-like shape makes bream hard to eat. The roach'southward streamlined body helps it apace swim away from danger. Since the hybrid is in between, information technology may not take either advantage.

Or maybe hybrids but aren't very smart. "They could exist sort of stupid and non react to the predator threat," Nilsson says.

Picky mating

Only because scientists notice hybrids doesn't mean the two species volition always breed with each other. Some animals are choosy nigh which mates they'll accept from another species.

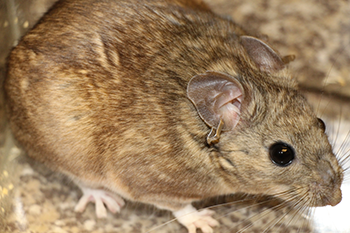

Marjorie Matocq studied this question in rodents called woodrats. Matocq is a biologist at the University of Nevada, Reno. She started studying California's woodrats in the 1990s. Matocq found these creatures interesting because they were very mutual, but scientists knew so little well-nigh them.

The desert woodrat (shown here) sometimes mates with a similar species chosen Bryant's woodrat. Researchers accept found that many hybrid offspring probably have a desert woodrat father and Bryant's woodrat mother.

M. Matocq

In a recent study, her team focused on two species: the desert woodrat and Bryant'southward woodrat. Both alive in the western United States. But desert woodrats are smaller and inhabit dry areas. The bigger Bryant's woodrats live in shrubby and forested areas.

At a site in California, the two species overlapped. The animals here were mating and producing hybrids, but Matocq didn't know how common this was. "Is it simply a take chances accident, or is this happening all the fourth dimension?" she wondered.

To notice out, the researchers brought woodrats to their lab. They gear up tubes shaped like a T. In each experiment, the scientists placed a female desert woodrat or Bryant's woodrat at the bottom of the T. Then they put a male desert woodrat and a male person Bryant'southward woodrat in opposite ends of the top of the T. The males were restrained with harnesses. The female could then visit either male and decide whether to mate.

Female desert woodrats almost e'er mated with their own species, the scientists plant. These females may have avoided Bryant's woodrats because those males were bigger and more aggressive. Indeed, the males oftentimes bit and scratched the females.

But the female Bryant'due south woodrats didn't heed mating with male person desert woodrats. Those males were smaller and more than docile. "There wasn't as much danger," Matocq observes.

Scientists Say: Microbiome

The researchers doubtable that many wild hybrids have a desert woodrat father and a Bryant's woodrat female parent. That could be of import because mammals, such as woodrats, inherit bacteria from their mothers. These bacteria stay in the creature'due south gut and are called their microbiome (My-kroh-By-ohm).

An animal'south microbiome may bear upon its ability to digest nutrient. Desert and Bryant's woodrats likely swallow different plants. Some of the plants are toxic. Each species may take evolved ways to safely digest what they chose to eat. And their microbiomes may accept evolved to play a role in that also.

If true, hybrids may have inherited bacteria that help them assimilate the plants that Bryant's woodrats typically consume. That means these animals might be better-suited to dine on what a Bryant's woodrat eats. Matocq's team is now feeding dissimilar plants to the parent species and their hybrids. The researchers will monitor whether the animals get sick. Some hybrids might fare ameliorate or worse depending on their mix of DNA and gut bacteria.

What'south exciting near hybrids is that you can call back of each i "every bit a little scrap of an experiment," Matocq says. "Some of them work, and some of them don't."

Source: https://www.sciencenewsforstudents.org/article/mixed-world-hybrid-animals

Posted by: calderaconere.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Two Conditions Must Be True For A Group Of Animals To Be Considered The Same Species"

Post a Comment